Why Tech Dependency on Big Platforms Is a Systemic Risk

Or how a malfunction in Northern Virginia can disrupt websites and organisations across the globe.

Welcome to ōmega, a newsletter on artificial intelligence beyond the hype. All content is written and curated by Roberto Pizzato — journalist, author, and consultant.

Born from a collaboration with fellow writer Cesare Alemanni, ōmega is also an Instagram page and a podcast, updated on an irregular basis.

For inquiries and feedback, please write to: rivista.omega@gmail.com.

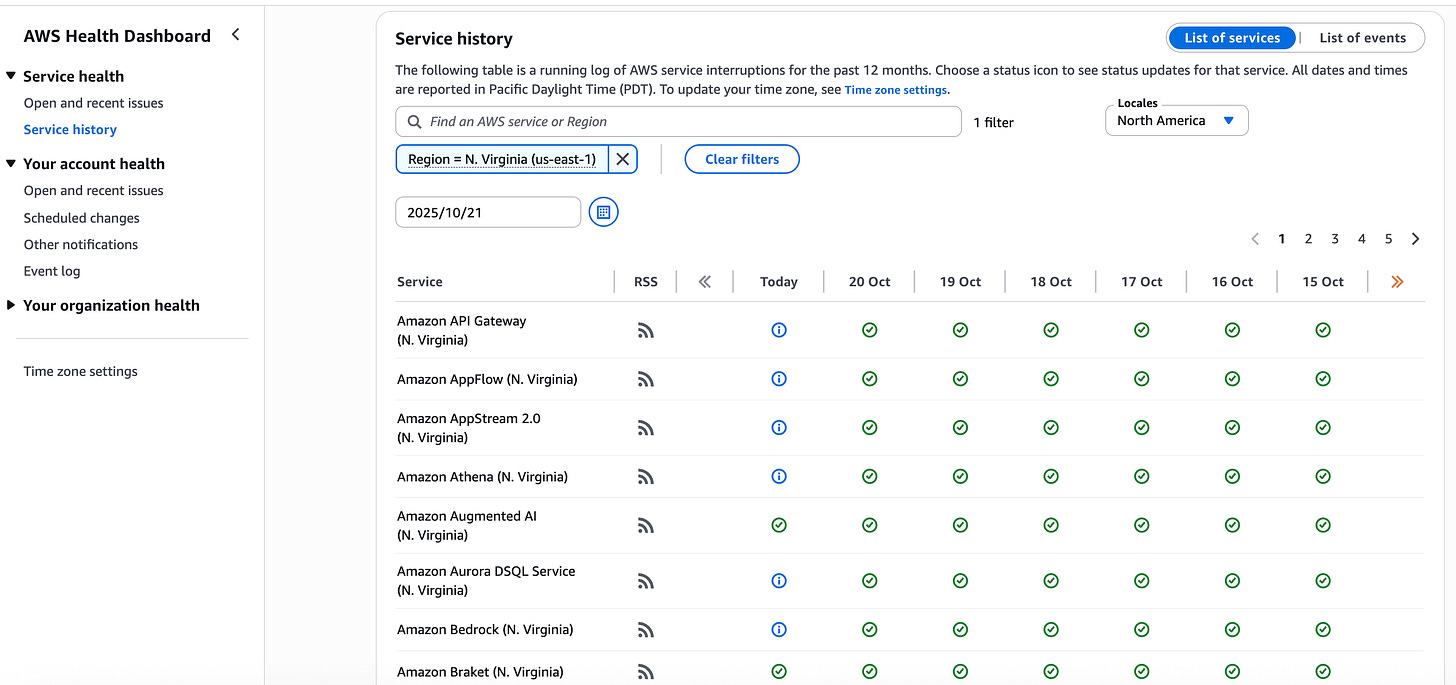

On October 20, 2025, an issue with Amazon Web Services (AWS) caused widespread disruption across much of the Western world, and beyond. In an instant, social media platforms like Snapchat, video games like Fortnite, encrypted messaging apps like Signal, AI services like Alexa and Perplexity, online payment apps like PayPal, banks like Lloyds, and even government websites like the UK tax agency HMRC went offline.

The problem originated in a datacentre in Northern Virginia that hosts Amazon’s cloud servers and triggered a global domino effect, once again exposing the fragility of our digital infrastructure.

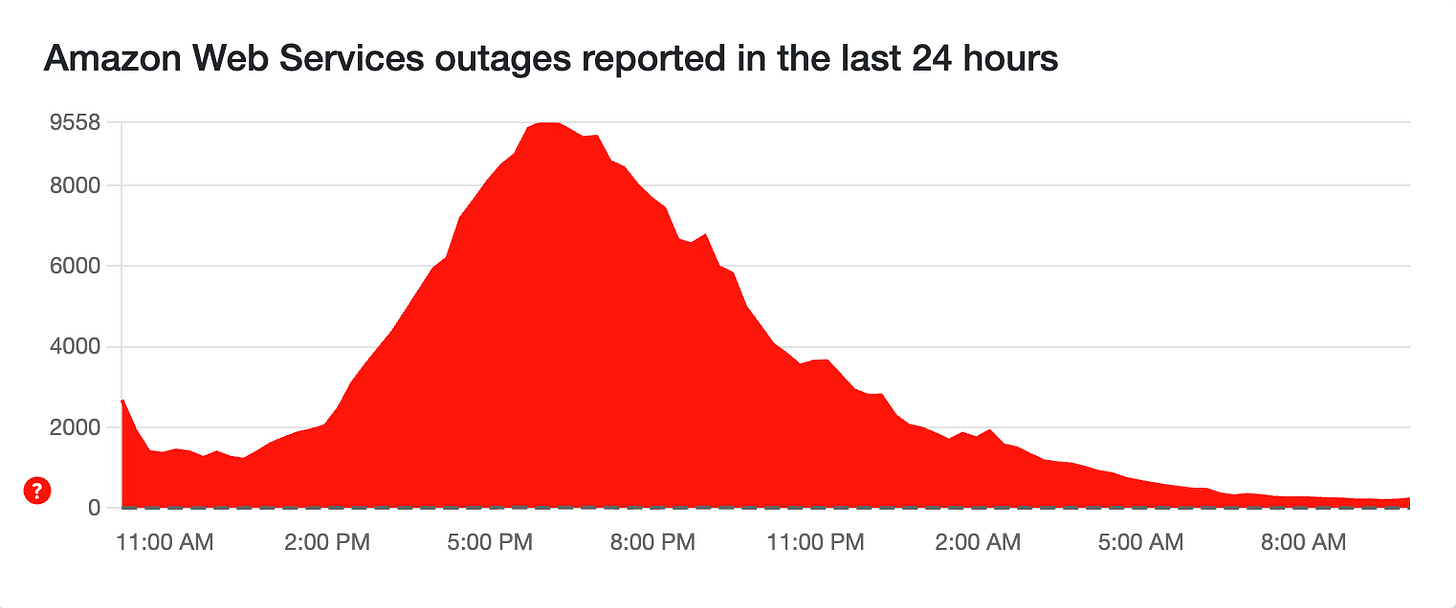

According to data from Downdetector, thousands of outage reports flooded in within minutes, while Amazon technicians worked to fix a DNS resolution issue affecting the DynamoDB service. The outage lasted several hours, and its effects could linger for days — from blocked corporate payments to delays in public services.

This is not an isolated incident. Similar outages have occurred in the past, often in the same AWS region. And every time, the same pressing question arises: have we built too much of our economy and security on infrastructure controlled by a handful of private companies?

Platform Capitalism

To understand the depth of the problem, we need to look at the very structure of the digital economy. As Nick Srnicek, author of Platform Capitalism, explains, our era is dominated by big platforms — a model in which a few tech companies build and control the fundamental infrastructure on which much of our economy depends.

This is partly the result of the U.S. government’s privatisation of the internet’s backbone in the mid-1990s, described by Wendy Chun in Control and Freedom: Power and Paranoia in the Age of Fiber Optics.

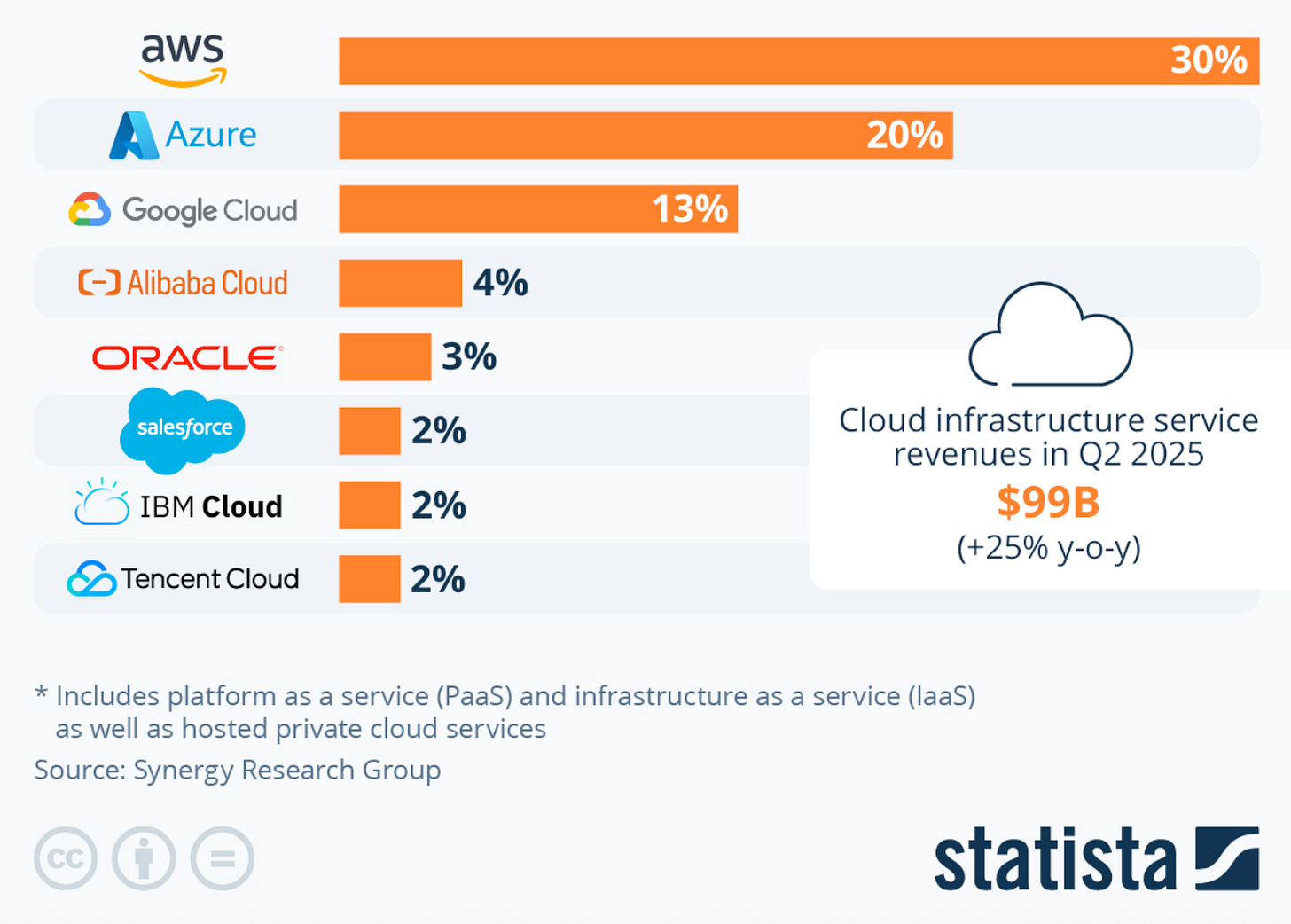

When it comes to the cloud, platforms like AWS (Amazon), Azure (Microsoft), and Google Cloud don’t just provide storage space or computing power — they’ve become the lifeblood of the global digital economy. According to the latest estimates, AWS alone powers around 30% of the global cloud market. If we include the other two, they control nearly two-thirds of it.

Behind nearly every website, mobile app, or banking system, one of these providers is almost always involved. And the bigger they grow, the more developers and companies become “locked in” to their ecosystems — switching providers can require massive resources. This is not just a technical issue. It’s a structural paradigm shaping how technological — and therefore economic and political — power is distributed around the world.

The Invisible Risk

When AWS went down, what we saw were not just “service disruptions”. If a cloud giant falters, the damage can become systemic.

Economic impact: Thousands of companies cannot complete transactions or pay employees.

Industrial impact: Digitised production and logistics chains can grind to a halt.

Financial impact: Payment platforms, crypto exchanges, and banking systems become inaccessible.

Critical services: Search engines and AI chatbots stop functioning.

None of this is coincidental. It’s the result of a long-term process. Digital technology is not only essential to U.S. GDP growth but also a strategic lever at the geopolitical, military, and financial levels.

This dependence on U.S. digital platforms paradoxically exposes everyone using their infrastructure — including allies — to significant risks. Despite the ubiquity of the internet and the cloud, datacentres are still physical places, and in the case of Big Tech, they are overwhelmingly located on U.S. soil.

A malfunction in Northern Virginia can bring down websites and organisations around the globe. And that’s not hyperbole: the October 20 outage revealed just how tightly woven our digital infrastructures have become.

It’s no coincidence that cloud and datacentres are also at the heart of Stargate, the $500 billion project involving computing power provider Oracle and OpenAI. The two companies are also tied by a $300 billion agreement — a project many analysts describe as a form of circular economy whose core could inflate an economic-financial bubble with ramifications extending from national security to pension funds.

Military Applications and National Security

There’s also the matter of the military’s use of the same cloud infrastructures — a connection that traces back to cybernetics and ARPANET, the precursor to the internet. The topic gained renewed attention during the recent Israeli-Palestinian conflict, when the interdependence between U.S. tech companies and Western militaries became more evident.

In the United States, the Pentagon signed the JWCC (Joint Warfighting Cloud Capability) contract in 2022 — a $9 billion deal with AWS, Microsoft, Google, and Oracle to provide cloud services for military use. Many intelligence agencies and foreign defence ministries also rely on the same commercial providers.

This means that a failure or cyberattack targeting a platform like AWS or Azure could compromise strategic national security functions — from military logistics to encrypted communications. The ability to quickly “migrate” to another system is often a myth: infrastructures are too integrated and complex to allow a swift transition.

An example can be found in the U.S. Navy: to move away from Azure, it would have to re-engineer its entire system, since the current architecture and its applications wouldn’t work with a different cloud service.

Platforms are not neutral tools: whoever controls the cloud controls the ability of entire nations to function — in peace and in war. The global economy rests on foundations controlled by a handful of private companies. It’s an efficient model — but also dangerously fragile. When a service like AWS goes down, it’s not just a website that crashes: factories, hospitals, public offices, and military systems can all grind to a halt.

Addressing this risk requires a paradigm shift. It’s not enough to talk about “cybersecurity.” What’s needed is a true digital infrastructure policy that prioritises resilience, diversification, and technological sovereignty, reducing our dependence on the big platforms.

This article was originally published in Italian for Wired Italy.

That’s all for now, thanks for reading! Share you comments and feedback as you please.

And drop your email below to subscribe to ōmega.